Grapes, Not Wines, Are Impacted by AVAs

There is a good case to be made that when comparing the French Appellation d’Origine Controlee (AOC) system with the American Viticultural Area (AVA) system, it is the American system of delineating grape growing regions that is far more invested in the theory of terroir than the French AOC system.

There is a good case to be made that when comparing the French Appellation d’Origine Controlee (AOC) system with the American Viticultural Area (AVA) system, it is the American system of delineating grape growing regions that is far more invested in the theory of terroir than the French AOC system.

This point concerning the relative commitment to terroir has been driven home to me while doing some work with the Petaluma Gap Winegrowers Alliance, which is currently in the process of developing a petition for AVA status for this region located in southwest Sonoma County. That petition, once developed and submitted, will provide information to the federal government (where AVAs are approved) on the climate, geography, soils and history of the Petaluma Gap region. It will be on this terroir-driven basis alone that the TTB evaluates the petition. In fact, these elements of a region have always been what was taken into account when an AVA has been approved by the federal government.

But consider the French AOC system. In order for a wine bottle to don the Chablis, Pomerol, Bordeaux Supérieur, Bâtard-Montrachet or any number of other appellations, much more than simply controls on where the wine’s grapes were grown come into play. The French AOC system goes well beyond simply drawing lines around a region. AOC rules, unlike AVA rules, dictate (or at least strongly nudge) a wine toward a specific style. AOC rules might dictate the age of the vines to be used, the amount or allowance at all of irrigation, the potential alcohol at harvest, or the specific grape varieties that may be used among other rules. America’s AVA rules do nothing of the sort. If approved, a Petaluma Gap AVA located on a bottle of wine will simply guarantee to the consumer that the wine in the bottle was made with grapes grown almost exclusively in the Petaluma Gap AVA.

The terroir-driven (and not style-driven) nature of the American Viticultural Area appellation system begs a question: Should an individual AVA be best understood by the impact the terroir commonly has on grapes grown there or should it be best appreciated for the character of the wines commonly resulting from grapes grown in the AVA? The former understanding of an AVA is much more helpful and even aimed at a winemaker’s perspective. On the other hand, the latter understanding of an AVA is much more consumer-oriented.

The problem, however, is that in trying to embrace an idea of what a specific AVA ought to produce in a wine, the lack of rules and regulations governing how grapes may be grown and how wine made be made that carry a specific AVA on the label means the likelihood that a wine is going to taste like what we think the AVA will make it taste like is up to the whims of a winemaker who is free to do whatever they want to do to the wine during production. Moreover, growers too can have a huge impact on either enhancing or obliterating any thread of character we may consistency expect to find in a wine hailing from a particular region.

And yet, despite the greater likelihood that a winemaker or grower can obliterate any character that should be inherent in a wine tied to a particular AVA in America, I would still argue the AVA system is much more terroir-driven than  the French AOC system with all its rules on grapegrowing and production. And this is precisely why I think it is safer to attempt to understand the American AVA as a region that commonly has a specific impact on grapes, rather than producing wines of a particular style. This is not, however the path that either the wine industry in America nor its more deeply interested consumers have followed.

the French AOC system with all its rules on grapegrowing and production. And this is precisely why I think it is safer to attempt to understand the American AVA as a region that commonly has a specific impact on grapes, rather than producing wines of a particular style. This is not, however the path that either the wine industry in America nor its more deeply interested consumers have followed.

Of course, understanding AVAs as descriptions of how a region’s terroir will impact grapes rather than how it will impact the wine is decidedly not consumer friendly. This understanding of AVA’s at best tells the consumer where the grapes that resulted in the wine came from. But that’s all. And this is exactly what the federal government meant AVA’s to convey to consumers when it instituted its federal AVA system.

Still, over the past 30 years and more winemakers and consumers and media have been trying to define AVA’s by the character of the wines produced from their grapes. Yet this is esoteric business and despite the efforts made, only very general conclusion about any AVA’s wines have been drawn. It’s notable that one of the most impressive websites every created (AppellationAmerica.com) had as its mission to explore this very question of AVAs impact on wine styles. Appellation America gathered the most impressive collection of wine writers ever assembled behind one editorial project. It failed to attract enough interest to remain financially viable.

One of the reasons I’ve come to believe that the most reliable way to understand AVAs is to focus on the impact an AVA’s terroir has on its grapes, rather than its wines, is from working with and paying careful attention to this region now seeking AVA status: The Petaluma Gap. Its climate is perfectly distinguishable due to the constant high winds that run through the Gap. When you talk to winemakers that work with Petaluma Gap fruit and with grape growers who cultivate grapes in the region, they can tell you with precision what impact these high winds and relatively cold temperatures have on the grapes. However, when you ask them what kind of impact the terroir has on the wines produced from these grapes, they hedge. They won’t tell you they don’t know, but they recognize that identifying the impact can’t be done with near the precision of identifying the impact of the terroir on the grapes. This is due mainly to the fact that winemaking techniques run the gamut and comparing one wine to another, even of the same variety, is difficult.

One of the reasons I’ve come to believe that the most reliable way to understand AVAs is to focus on the impact an AVA’s terroir has on its grapes, rather than its wines, is from working with and paying careful attention to this region now seeking AVA status: The Petaluma Gap. Its climate is perfectly distinguishable due to the constant high winds that run through the Gap. When you talk to winemakers that work with Petaluma Gap fruit and with grape growers who cultivate grapes in the region, they can tell you with precision what impact these high winds and relatively cold temperatures have on the grapes. However, when you ask them what kind of impact the terroir has on the wines produced from these grapes, they hedge. They won’t tell you they don’t know, but they recognize that identifying the impact can’t be done with near the precision of identifying the impact of the terroir on the grapes. This is due mainly to the fact that winemaking techniques run the gamut and comparing one wine to another, even of the same variety, is difficult.

I suspect winemakers in most AVAs, even those like the Petaluma Gap that are well-drawn, have the same problems.

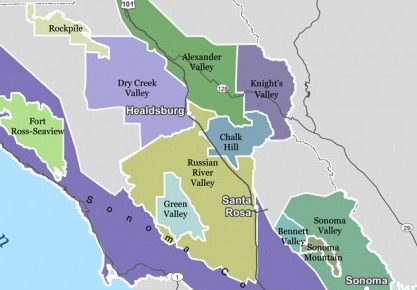

The only solution to the problem of making AVAs consumer friendly is study. Regular, consistent, rigorous study of wines produced from grapes grown within a particular AVA. Some AVAs, being so large and having such a diverse set of terroirs within them, won’t lend themselves to this kind of study. However, AVAs like Green Valley in Sonoma County, Fort Ross-Seaview in Sonoma County, Atlas Peak or Spring Mountain or Howell Mountain or Mt. Veeder in Napa Valley, or the coming Petaluma Gap AVA are drawn in such a way that after many years of careful study, we may in fact be able to say what type of character a wine is likely to possess if winemaking or grapegrowing techniques are not too terribly overbearing.

However, until these kinds of long-term studies are conducted, the most reliable thing we are likely to be able to say about an AVA is that its terroir will have a certain impact on grapes grown within it.

Great post Tom. We are weighing these issues in McLaren Vale. We’re a few years into a 10-20 year annual vintage tasting study of un-oaked wines from a sub-district map built up from geology and soil mapping to test our theory. Realising we need to add more layers – topo, temps, rainfall, wind – and lots more sensory data before we can be very conclusive. Fascinating stuff.

Dudley,

I would really like to hear more about your project. I am a winegrower in Sonoma County’s Russian River Valley AVA and we are about to embark on a multi-year project that aims to define neighborhoods within the AVA. Tradition has led to the naming of several sub-regions that have different personalities that we believe are due primaraliy to climatic differences but also due to the myriad of other physica differences such as soill Howeverno one has ever actually tried to tie it all together. We will be starting with pinot noir as it is not only widely planted, it is also better understood than many other varieties and is by its nature somewhat transparent.

Hello,

great article indeed.

One reflexion : having some common production rules in an AVA maybe allows the consumer to feel more accurately the characteristics a given terroir brings ?

Seems to me that if you want to make U.S. AVA’s more consumer friendly, then the consumer would have to be able to recognize the characteristics of the AVA in the wine. The only way that will happen is if the U.S. adopts more stringent viti and vinification guidelines for each AVA. Do we really want that?

Ron:

No…I don’t. I think that would be unAmerican. And the American AVA system matches well with the American disposition.

Great discussion, it is about grapes. Take a long look at the Lodi Natives project that eleminated winemaking maniplulation (natural yeast, NO ADDS and neutral wood) to demonstrate vineyard specific character. The result defines a lot.

What was the result Roger?

The bigger problem is that the boundaries of most AVAs are defined primarily by marketing, political, and social interests and typically do NOT coincide with pronounced breaks in geographical and geologic characteristics (geologic contacts, soil series boundaries that can and should be utilized to delineate physical terroirs. As a result, due to the huge variations in topography, elevation, bedrock, and soil type, the phrase “Napa Valley terroir” or “Columbia Valley terroir” when used in reference to the AVA is ludicrous. True physical terroir can only be experienced on a much smaller scale – and certainly not on the scale of the average AVA. Even the smallest AVA in the US (Cole Ranch, <200 acres) contains 8 different soil series. The effort to create truly terroir-driven AVAs is actually impeded by TTB rules which do not allow contacts between different geologic units or soil series to function as AVA boundaries.

Kevin:

So the concept of AVA”s in the U.S, are all about money? I tend to agree. If we cannot distinguish the Cabernets of Mt. Veeder from Howell Mountain, then why have AVA’s at all?

Of course they’re all about money – as they are in Europe and elsewhere. All romance aside, they’re really just a device for creating and/or protecting a valuable brand. I don’t think anyone has ever petitioned for an AVA just because they were excited about terroir. The way in which one delineates the area that defines the brand (AVA) can be true to terroir or it can ignore it. Most current AVAs actually consist of sets or collections of terroirs that share some sort of vaguely defined theme that may or may not actually have a detectable influence on the grapes and wines from that place.

Very interesting article. The metrics of terroir are very slippery indeed. I, for one, would like to see a GIS study done for just one region, such as Paso Robles, with a focus on the grapes (or pick a single varietal such as Cabernet Sauvignon ) from each of the new AVA’s plus York Mountain, in order test if there really are significant telling differences in the grapes. What a great project for some Viticulture / Oenology School.

As Coombsville AVA author, winemaker, grape grower and total honk, i will assert that our little AVA does offer a regional character that many people tell ME about. We do have a relatively uniform climate and soil profile which certainly creates a common thread amongst the wines from our sub-appellation. As a consumer, I’m grateful for the system and people love to know the region from which wines have come. Unlike France, we have little history and no restrictions on grapegrowing, varietals, trellising, harvest timing, etc. The French version here would be considered un-American. Lots of French winemakers like our system and have moved to our land of opportunity and creative freedom.

It’s not hard to envision, in maybe 50-100 years, something like Oakville becoming east, middle and west. Sad for Sonoma that the debates over AVAs have spanned decades with different interests and epochs of what they are (I used to work in Dry Creek, which is a sound AVA except the part that should be Russian River). Petaluma Gap makes lots of sense except for the gerrymandered “Sonoma Coast” sub-AVA overlay. Time for a do-over

Great piece Tom and thoughtful as always. After 35 years in this industry and having visited and tasted in multiple countries I do believe in somewhereness. I do believe that place matters. But what I do not believe is this- we wine consumers do not know anything about this topic of terroir and likely never will. I am referring to the 99% of drinkers of course that know Places like Australia, France, Napa or Sonoma, South America, South Africa etc. but will not likely have a feel for the hundreds of or make that thousands of vit areas out there. It is the most confusing detail in selecting wines yes? How many times has Russian River been redrawn and why? 11 new places to learn in Paso Robles when its reputation is finally a good one? Tis mainly marketing to help sell the wines. Our system is a good one here in the new world and we all need to continue the education process long term. Good grapes make good wines….

It seems clear that the AOC system is, by design, infinitely more devoted to the concept of terroir. The seemingly draconian regulations put in place by the INAO aim at isolating variables, so that geographic delineations are more meaningful, no?