The Rise of Willamette Valley’s Sub-Appellations — Statistically Speaking

Since writing about the proposed conjunctive labeling law in the Oregon legislature meant for wines produced in the Willamette Valley, I’ve been thinking a lot about the Willamette Valley. I continue to believe that the proposed conjunctive labeling law that will require all wines carrying any of the sub-AVAs located in the Willamette Valley on their label to also place the words “Willamette Valley” somewhere on the label, is imprudent.

Since writing about the proposed conjunctive labeling law in the Oregon legislature meant for wines produced in the Willamette Valley, I’ve been thinking a lot about the Willamette Valley. I continue to believe that the proposed conjunctive labeling law that will require all wines carrying any of the sub-AVAs located in the Willamette Valley on their label to also place the words “Willamette Valley” somewhere on the label, is imprudent.

However, I’m a bit less concerned today about this conjunctive labeling proposal given that the bill that would advance it, SB 829, explicitly notes that “Willamette Valley” need not “(a) Be included in or near the appellation of origin; or (b) Be in the same size or font as the appellation of origin”. In other words, if the winery wants to hide the term “Willamette Valley” somewhere on their label rather than putting it front and center alongside, say, Dundee Hills or McMinnville, they can do that.

Among the claims that have been put forward by the proponents of this bill is that over the years the term “Willamette Valley” has been replaced by reference to the smaller, sub-AVAs of the Willamette Valley and that “Willamette Valley” is more and more left off the labels. Claims like this often go unchallenged or even unchecked. I checked.

The proponents are right.

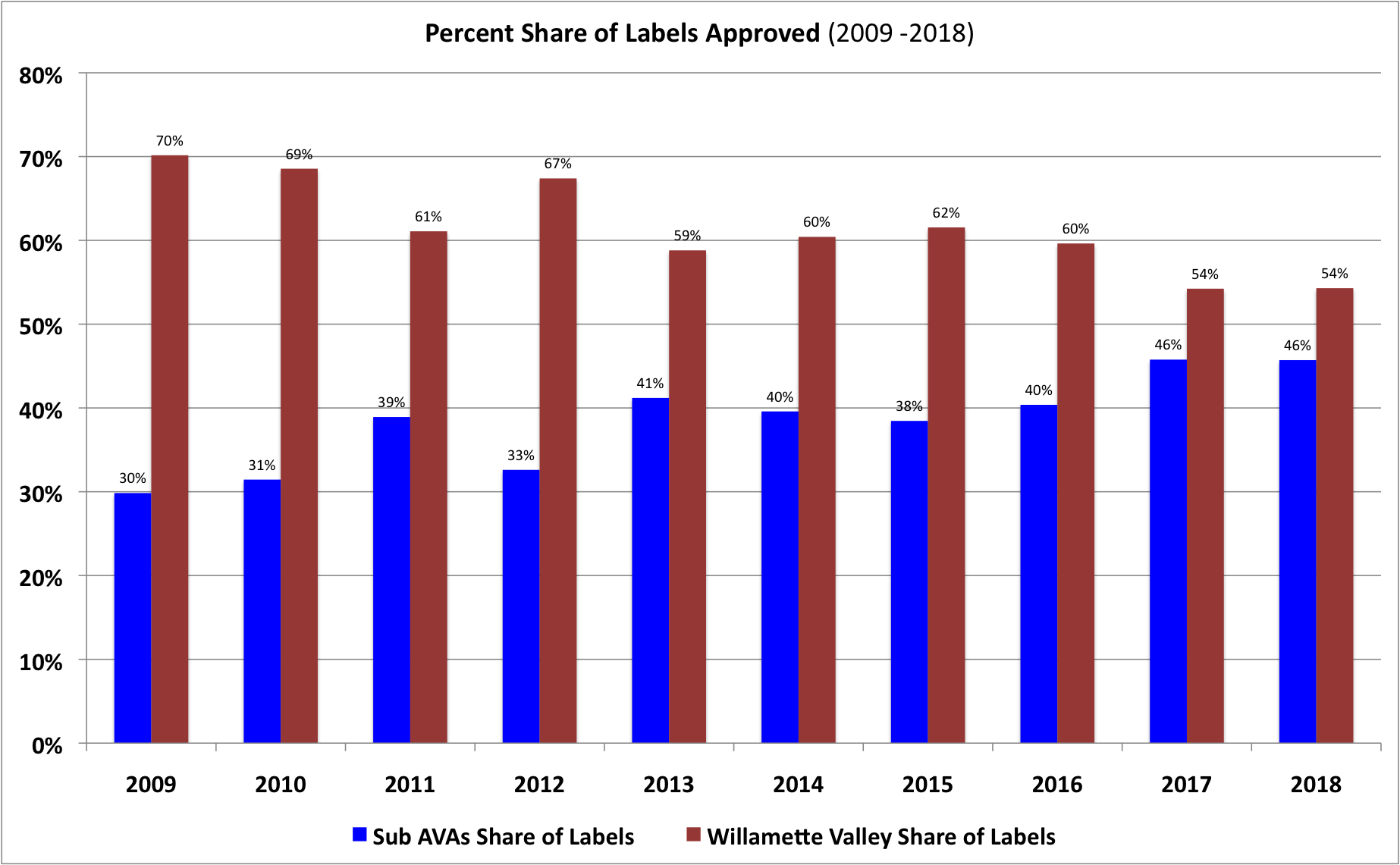

Over the past decade, the percentage of labels approved for use by the TTB that were for wines produced with Willamette Valley grapes and that identify a sub-AVA other than the larger “Willamette Valley” AVA has indeed increased.

In 2009, just under 30% of wines labels approved by the TTB and meant to be placed on a wine produced with Willamette Valley grapes carried only a Willamette Valley sub-AVA (Dundee Hills, Chehalem Mountains, McMinnville, etc.). In 2018 over 45% of wines produced from grapes grown in the Willamette Valley held a Willamette Valley sub-AVA on its label. Put another way, in 2018, nearly half of all wines produced with grapes grown in the Willamette Valley did not mention “Willamette Valley” as their official appellation of origin.

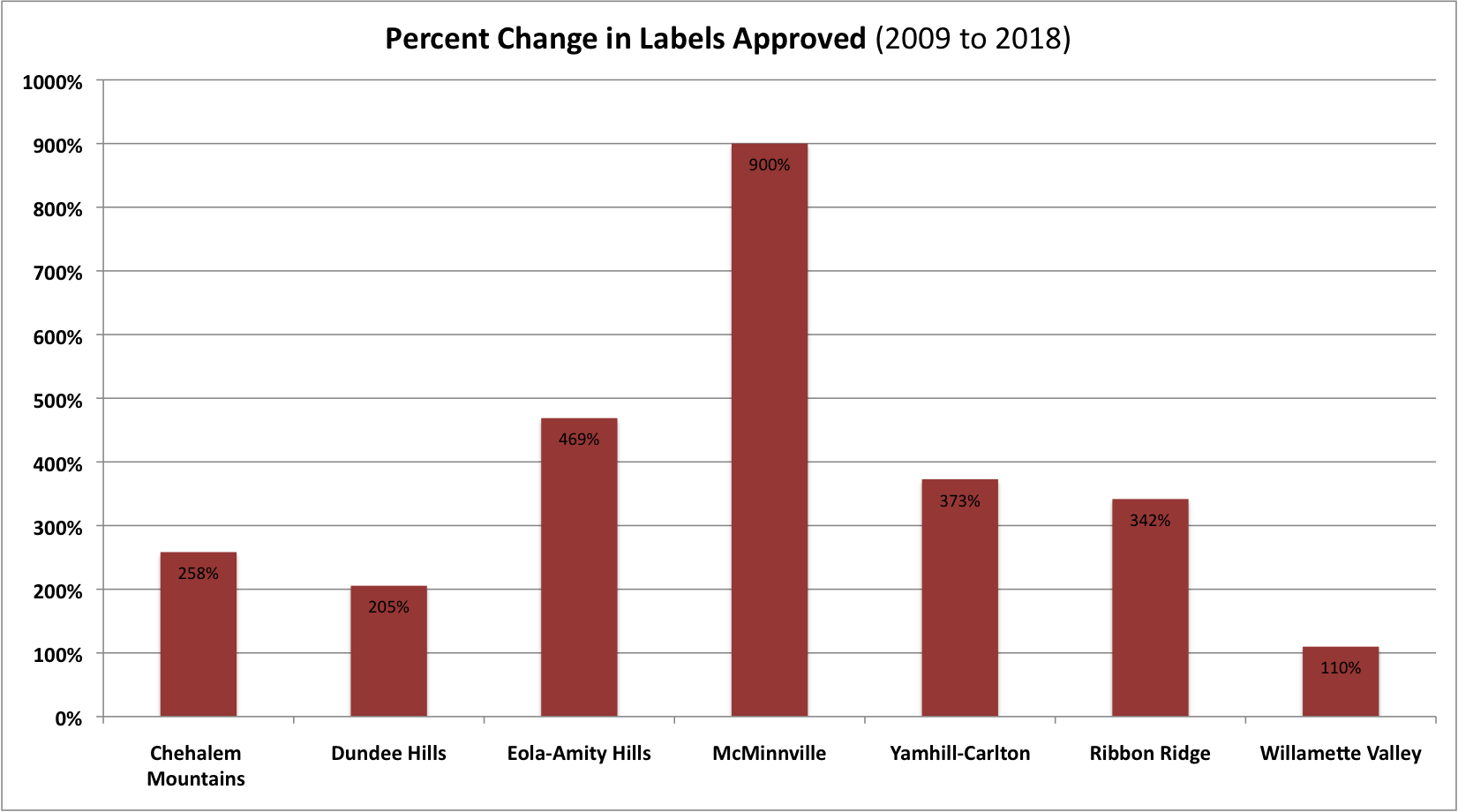

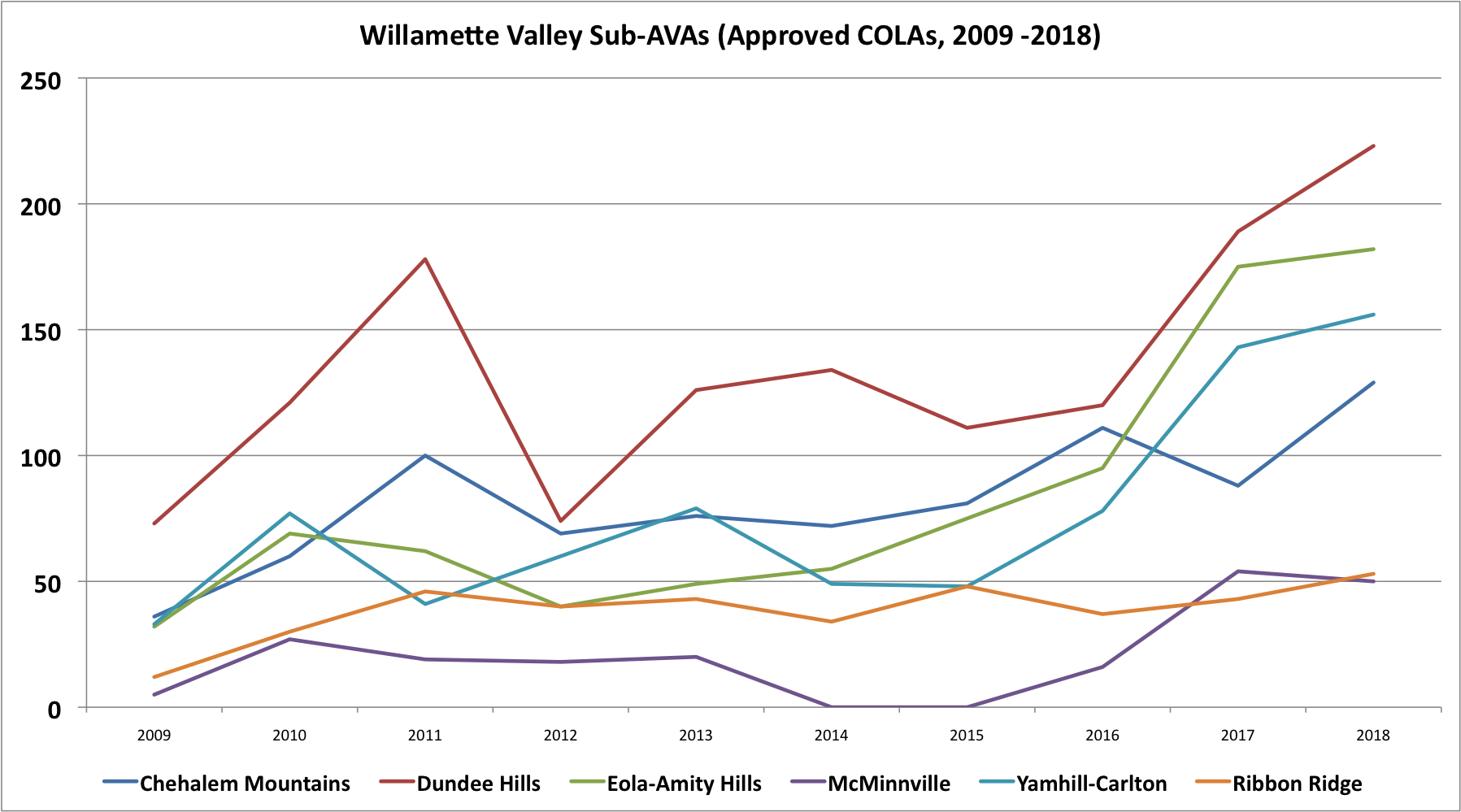

Another way to look at the rise of Willamette Valley sub-AVAs is to observe the increase in use on labels of the individual AVAs compared to the  increase in the use of just “Willamette Valley” on labels. From 2009 to 2018, labels approved for use carrying the larger “Willamette Valley” AVA increased 110%. However, use of only sub-AVAs on labels collectively increased by 315%. A look at the 2009 to 2018 changes in use of the individual sub-AVA use on labels tells another story.

increase in the use of just “Willamette Valley” on labels. From 2009 to 2018, labels approved for use carrying the larger “Willamette Valley” AVA increased 110%. However, use of only sub-AVAs on labels collectively increased by 315%. A look at the 2009 to 2018 changes in use of the individual sub-AVA use on labels tells another story.

Chehalem Mountains: Up 258%

Dundee Hills: Up 205%

Eola-Amity Hills: up 469%

McMinnville: Up 900%

Ribbon Ridge: Up 315%

Yamhill-Carlton: Up 373%

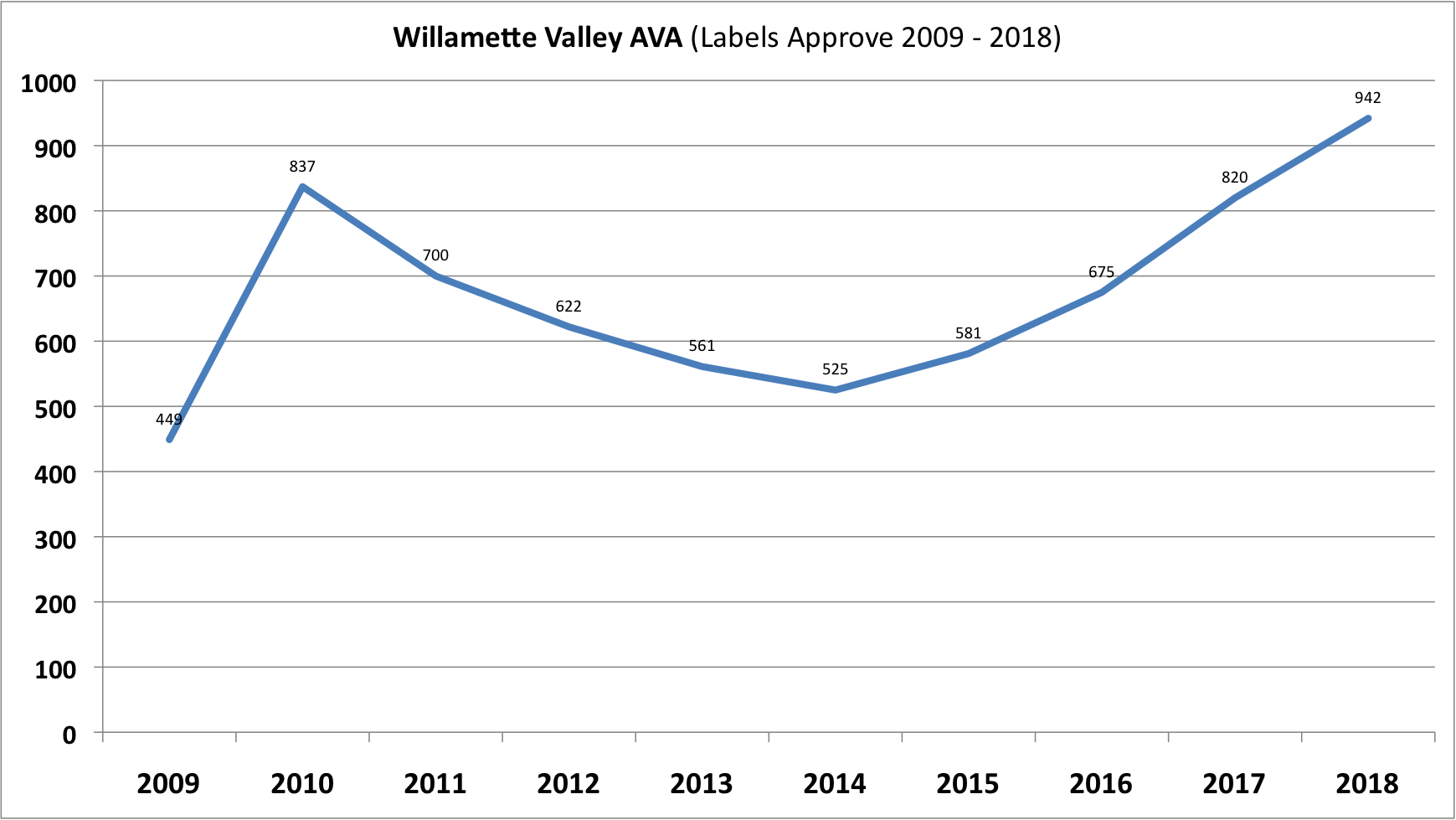

Growth in the use of all the individual Willamette Valley sub-AVAs significantly outperforms the growth in the use of the larger “Willamette Valley” AVA on a label during the 2009-2018 time frame. What’s really noteworthy is that if you look at the growth of labels approved for use holding the larger “Willamette Valley” AVA from a slightly shorter timeframe, between 2010 to 2018, you notice a mere 13% increase as a result in a significant spike in “Willamette Valley” labels in 2010.

In using the COLA (Certificate of Label Approval) database to track the changes in use of the various sub-AVAs in the Willamette Valley and the larger Willamette Valley AVA, what’s clear is that Oregonian vintners very rarely used both the sub-AVA and the larger Willamette Valley AVA on their labels. In a few cases, a wine labeled with a sub-AVA mentions the larger “Willamette Valley” AVA on its back label copy, but this isn’t so much to identify the larger AVA but to place the sub-AVA or a vineyard in a larger context.

Vintners use smaller, sub-AVAs on their labels rather than the larger AVA (which they could if they chose) in order to associate their wine with a more well-defined and in most cases more highly valued and appreciated region. This clearly happens in the Willamette Valley as well as in Napa Valley, Sonoma County, and Mendocino County, to name just a few important winegrowing regions.

Vintners use smaller, sub-AVAs on their labels rather than the larger AVA (which they could if they chose) in order to associate their wine with a more well-defined and in most cases more highly valued and appreciated region. This clearly happens in the Willamette Valley as well as in Napa Valley, Sonoma County, and Mendocino County, to name just a few important winegrowing regions.

That the wines and grapes from the smaller, nested Willamette Valley sub-AVAs are more valuable than wines and grapes that carry the larger Willamette Valley AVA could be demonstrated by the price per ton that is paid for grapes with a sub-AVA provenance versus the price per ton paid for grapes with the larger Willamette Valley AVA. Unfortunately, the annual Oregon Vineyard and Winery Report produced by the Institute for Policy Research and Engagement at the University of Oregon Eugene does not track average price per ton paid for the sub-AVAs. Its annual report looks at the price per ton paid by only “North Willamette Valley” and “South Willamette Valley.

However, it turns out that that the six Willamette Valley sub-AVAs land in the “North Willamette Valley” for the Report. What we find is that in the 2017 Oregon Vineyard and Winery Report North Willamette Valley Pinot Noir averaged $2,534 per ton. South Willamette Valley Pinot Noir averaged $2,264 per ton.

Another source of information concerning the average price per ton paid for Willamette Valley grapes is GrapeConnect, a clearinghouse for  grapes offered for sale. In their 2018 Harvest Report on average prices offered per ton for different AVAs on their website, you see a clear “sub-appellation premium” for Pinot Noir grapes offered in each sub-AVA versus Pinot Noir Grapes that carry the larger Willamette Valley AVA. Keep in mind, this is a very unofficial assessment of value.

grapes offered for sale. In their 2018 Harvest Report on average prices offered per ton for different AVAs on their website, you see a clear “sub-appellation premium” for Pinot Noir grapes offered in each sub-AVA versus Pinot Noir Grapes that carry the larger Willamette Valley AVA. Keep in mind, this is a very unofficial assessment of value.

Average Offer Price on a Ton of Pinot Noir in 2018 by Willamette Valley AVA/Sub-AVA at GrapeConnect

Ribbon Ridge: $3,727

Dundee Hills: $3,022

Chehalem Mountains: $2,630

Yamhill-Carlton District: $2,666

Eola-Amity Hills: $2,449

McMinnville: $2,874

Willamette Valley: $2,129

The point, in the end, is that like in so many other aspects of culture, academics, and commercial life, specialization is becoming the norm. The same is true in wine. Even when the Willamette Valley Conjunctive Labeling bill becomes law (and it will), the use of Willamette Valley sub-AVAs on labels as the primary appellation of origin will continue to grow. I’d be shocked if in five years there are still more wine labels approved with the Willamette Valley as the primary appellation of origin than labels approved with sub-AVAs as the primary appellation of origin.

This is not to say that the Willamette Valley AVA is the equivalent of the “Central Coast” AVA in California, a gigantic AVA that primarily is the source of low cost, average wines. In fact, the larger Willamette Valley AVA has a rather stellar reputation for wines of quality and particularly Pinot Noir. However, it seems likely that over the next decade or more this stellar reputation will be taken advantage of with plantings on the valley floor rather than on the hillsides.

History has shown that the Willamette Valley made its reputation from grapes grown in vineyards on the hillside slopes of the Western part of the Valley. Valley floor vines are more vigorous and produce grapes of lesser quality. Nonetheless, such wines are eligible to carry the “Willamette Valley” AVA.

It seems far more likely that any damage done to the reputation of the Willamette Valley wines will happen as a result of valley floor plantings than a continued migration by quality growers to using only the sub-AVAs on their labels. Yet I’ve heard of no proposal in the works to limit plantings on the floor of the Willamette Valley. Rather, it has been the creation of the sub-AVAs that gave growers and winemakers of the Willamette Valley appellations not susceptible to bastardization.

When the conjunctive labeling law passes later this year it will create a circumstance where a more and more reputation-challenged “Willamette Valley” AVA is forced upon growers and winemakers using the more stringently regulated sub-AVAs. The goal of the conjunctive labeling project is to preserve the reputation of the larger Willamette Valley AVA by usurping the higher quality reputation of the sub-AVAs. Time will tell if this will work.

Awesome research Tom, thank you. The points you make are well taken. There was thought given to setting a WV AVA minimum elevation boundary. I wish we had caught it when the original application was submitted. Later Sub AVA applications did include a minimum elevation. Interesting puzzle to solve. Glad you are in Oregon now, perhaps your thoughts will stimulate innovation.

Curious to know what the proposed minimum elevation was going to be. Interesting article.

Also, if there were a change to the Willamette Valley AVA with regard to elevation, wouldn’t you need to grandfather in all those who have already planted on the floor?

I agree with Jim. I consider Tom one of the wine industry’s foremost pundits. Now that he has cast his eye on Willamette Valley and Oregon, we’re certain to have much and more engaging commentary from him.

Tom, first WELCOME to the Willamette Valley! I am curious your thoughts on conjunctive labeling in Napa and Sonoma. Good? Bad? Indifferent?

The reasoning behind the effort to include the Willamette Valley AVA in our labeling for sub AVAs within the Willamette Valley is that we were wrong in going so strongly to identifying our smaller AVAs before they had recognition on the world stage. China knows that the Willamette Valley equals quality Pinot noir. China does not know the sub AVAs. I count myself wrong in not understanding this earlier.

Hmmm? Not only conjunctive but a conundrum! Those of us living in a different country (or two) notice that the name Willamette means something to the run-of-the-mill consumer, especially for Pinot, but Ribbon Ridge or Yamhill-Carlton means zip. Wine geeks might get the sub-AVAs, but, even within the wine trade, many people do not. So, perhaps having Willamette somewhere in the fine print is not necessarily a bad thing?

Ken, thanks for commenting.

I guess I’m not clear what you are saying. Is it that it was a mistake to apply for AVA status for the sub-AVAs before the regions had gained certain recognition without TTB approval or that it was a mistake to promote them heavily after they had achieved their official status. Either way, the “Sonoma Coast” AVA might be instructive here. It is a sub-AVA of Sonoma County and lasted for some time before the various smaller AVAs you now see bing approved were thought to be carved out. Sonoma Coast gained recognition for Pinot Noir and then it became clear that there were areas inside that AVA that were distinctive. And now we see them being officially recognized. Petaluma Gap comes to mind. There was a good deal of talk about the Petaluma Gap well before the wineries there applied for AVA status –which they received.

Eugenia,

Thank you for the welcome. We are really enjoying getting to know our new home. But I must admit, I’m jonesing to have more opportunities to play golf.

As a rule, I’m not a fan of any conjunctive AVAs, whether in Napa, Sonoma, Paso or Willamette. I beleive they illegitimately usurp individual producers’ marketing freedom. Dundee Hills is a legitimate, recognized AVA. A winery there, if they believe their brand or wine’s reputation or perception is diminished by inclusion on the label of “Willamette Valley” ought to be allowed to exclude mention of the Willamette Valley. As I mentioned in this post, the impact of the usurpation is mitigated by the law allowing a producer to place “Willamette Valley” anywhere on the label they desire, rather than having to put in on the front of the label next to the Sub-AVA. Sonoma County does this also I believe.

As you understand, a wine’s label is very important real estate. When they are forced to give that real estate over to another entity in an uncompensated way, that’s just not fair in my view.

Helene,

If Ribbon Ridge or Dundee Hills or McMinnville is less known overseas or by most wine drinkers, and if it is determined that it needs to be better recognized for the sake of those using the AVA on their label, then their is a solution: market the AVA better.

I work in a restaurant in NYC. I have a very well-heeled customer base. They drink fine wines from around the world. Some are still confused about the difference between Margaux and Chateau Margaux. They aren’t familiar with Mt. Veeder or Atlas Peak. However, they do know Napa Valley and appreciate the perceived safety of purchasing from that appellation. When it comes to Oregon the number of people who can articulate sub-appellations is less than 1 in 1000. They come in asking for Oregon wine and “Oh I like Willamette Valley.” Consciousness of Eola or Amity is basically non-existent. To remove the safety net of Willamette from those labels is, in my opinion, not a good idea. Ever hear of “Like a deer in the headlights?” That is the look my customers have until I explain to them the use of the sub-appellation in Oregon. I am educating your customers and my clients. To many of them it requires an expense of mental capital they aren’t ready to spend. When I look at a bottle of Burgundy I seen not only the name of the appellation (and the vineyard) but also “Grand vin de Bourgogne”. Why not look at “Willamette Valley” as the “Grand vin de Bourgogne” for Oregon wine from that region? Use it as a clarifier. I don’t think consumer recognition has caught up the with desire of winemakers yet. Best to take it a little slower and maybe spend some of that pent up energy on a broad public education project.

Hi PW…

One thing that may not be clear in what I wrote is that currently and without any new law, wineries in the Willamette Valley’s sub-AVAs may, if they like, include “Willamette Valley” on their labels alongside the sub AVAs they are using (Eola, Dundee, McMinnville, etc.). The new bill, when it becomes law, will REQUIRE any winery using a sub-AVA to also put “Willamette Valley” somewhere on their label.

All of that is to say that nothing is being “removed”. Wineries are free now to include both the sub-AVA and the larger Willamette Valley AVA…if they choose.

Lovely set of comments on what is clearly (at least in/for the Willamette) a contentious issue!

I suppose that PERMITTING the use of ‘Willamette Valley’ as well as a sub-AVA is a sound compromise, and I suppose I agree that REQUIRING ‘Willamette Valley’ on the label of any sub-AVA is rather silly. But, most/all of the sub-AVAs don’t really have the wherewithal to afford to promote a sub-region, do they?

As part of an MW Dissertation, one of my students investigated the sub-AVAs and whether a VERY experienced panel of mostly MWs and senior wine trade professionals could place 24 wines in their respective AVAs. Jancis was top scorer with 13; I think I identified 8 correctly. Most tasters identified 5 or 6. Although I missed out the correct sub-appellation for one of the wines, I did identify the producer, almost certainly because I know their wines well. No extra marks, however!

What might be worthwhile, at least in foreign markets, is a strategy which promotes all the sub-AVAs as higher quality (to match the higher prices)? Then when the south of the Willamette is planted and producing, some consumers might be minded to trade up?

Or, as in Burgundy, KNOW the producer and the wines thereof. ‘Pinot Noir, the Holy Grail, Some may find it; some may fail…’

In general, I’m a big advocate of giving consumers more useful information. So to that extent, I love the idea of Oregon producers adopting conjunctive labeling so that a person who is not familiar with something like the Eola-Amity can connect it to something they are familiar with–like the Willamette Valley.

But, like Tom, I get hung up on the “required” part that mandates the conjunctive labeling. While the use of conjunctive labeling just seems like good business sense, I truly don’t think it is the government’s role to mandate good business sense.

Wineries learn marketing through trial and error and, for some, they may have no issues selling their wines locally without using conjunctive labeling. But for those with more ambitions and bigger visions, let them take the lumps to learn on their own that customers outside of Oregon (or the Pacific Northwest) need a little more context on their label to know that wines from Ribbon Ridge, McMinnville, et. al. are worth paying the same premium they’re willing to spend to get a great Pinot from the Willamette Valley.

The only well-controlled quantitative research that I know of on conjunctive labeling was done with Sonoma appellations, and it conclusively showed conjunctive labelling did not hurt the sub-AVAs and in some cases helped. Perhaps the results would be different in Willamette Valley, although I suspect not. This is not a difficult issue to test, and some hard numbers might help settle what is sometimes a contentious issue. That said, even well-designed research can’t address Tom’s philosophical dispute with conjunctive labeling.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.com/cs/register?ref=RQUR4BEO