A Tale of Crime, Greed, Stupidity and Excess in the Wine World

Among those arts and crafts that inspire possession by collectors and connoisseurs, wine is the only one that cannot be appreciated and experienced collectively. Wine also delivers the shortest period during which a collectible can be experienced. While a Picasso will be experienced and appreciated for ages as long as visual images are preserved, a wine can only offer its true nature from the time it is opened until consumed.

Among those arts and crafts that inspire possession by collectors and connoisseurs, wine is the only one that cannot be appreciated and experienced collectively. Wine also delivers the shortest period during which a collectible can be experienced. While a Picasso will be experienced and appreciated for ages as long as visual images are preserved, a wine can only offer its true nature from the time it is opened until consumed.

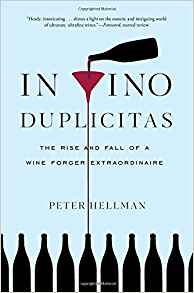

I mention this important fact in the context of recommending Peter Hellman’s superb new book about the Rudy Kurniawan affair, In Vino Duplicitas: The Rise and Fall of a Wine Forger Extraordinaire.

Off the bat, I do want to say that I take issue with the title of Mr. Hellman’s new book. Based on everything he reports and describes (and its substantial) Mr. Rudy Kurniawan was not a very good forger of fake wine. The mistakes he made that led to his downfall and eventual conviction were extraordinarily amateurish. He appeared to have too little appreciation for the most basic detail.

Consider that at the 2008 Acker Merrall auction that would lead to his downfall, Kurniawan had the auction house selling a bottle of 1929 Ponsot Clos de la Roche, a wine that was not produced under the Ponsot label until 1934. Kurniawan also consigned to the auction house over 3 dozen bottles of Ponsot’s Clos Saint-Denis, from vintages 1945 through 1971. Yet the winery didn’t start making this wine until the 1980s.

A better title for Hellman’s book would be “The Rise and Fall of a Prodigious Wine Forger” as it appears that while Rudy was not an extraordinary criminal, he did put is nose to he grindstone and pump out a hell of a lot of fake wines.

The real benefit of Hellman’s book is its ability to transport us into a society of wine collectors that very few will ever experience or understand. The sheer excess that is on display in Hellman’s recounting of the pre-recession years when the auction market boomed on the back of the elite’s ravenous capitalism and insane earnings goes well beyond normal conspicuous consumption. Hellman details this period in sober but highly descriptive prose, ranging from the bacchanalian dinners collectors threw for their cohorts at which bottles worth tens of thousands of dollars were uncorked late into the night to the excessive affairs that were carried out under the auspices of wine auction houses.

Yet even with Hellman firmly and deliberately at the helm describing this era and people for us, it is very difficult to completely appreciate, let alone know, this kind of excess.

In Vino Duplicitous is part true crime story and part portrait of a psychopath, because that’s clearly what Rudy Kurniawan was. In addition to forging rare wines at an awesome rate, he also wine, dined, feted and befriended the wine collecting elite while at the same time lying to their face, stealing from them, taking their money off of them and defrauding them.

Toward the end of the book, Hellman makes the best possible attempt to explain how anyone could possibly give Rudy any kudos even after the truth came out. Rudy’s generosity is cited along with his charm and down to earth demeanor. Yet, the evidence Hellman compiles in the book indicates that Rudy had no allegiance to anyone and that all or most of his generosity and charm can be chalked up to a con man’s long game.

There are those who come off quite nicely amongst the fraudulent shenanigans. Don Cornwell, the attorney and Burgundy lover, is the straight arrow defender of the defrauded. The detectives and U.S. attorneys come off as competent and dedicated. And of course, Laurence Ponsot is the hero.

However, it is difficult to muster too much sympathy for Rudy’s victims. Many of them profited off his acquaintance despite not necessarily knowing his crimes. Others are simply so prodigiously rich and careless and dumb with their money that their accumulation of fake wines and the loss of the millions they paid for them is a difficult thing to care too much about.

The wine industry is nearly without any intrigue, scandal or mystery. As a trade, it’s a rather somber institution. Sometimes hail destroys vineyards. There are occasional arrests for unscrupulous financial dealings. But in all, it’s not much to look at. That’s the primary reason the Kurniawan Affair drew so much attention outside the usual wine publications.

Hellman’s In Vino Duplicitous ought to turn out to be the last word on the affair. He covered the story for the Wine Spectator magazine as it broke and it’s clear that in the process of turning that experience into this book he went the distance. He admits that one primary question remains: Did Rudy do this alone? The experts, Hellman reports, are split on this question. And there is no evidence to tip the scales in either direction and certainly no indication from Kurniawan.

Nevertheless, the case is open and shut and Hellman’s rendering of it, start to finish, is superb.

At the beginning of this review, I note the difference between wine and other collectibles. I point this out because it’s notable and a unique factor where collecting wine is concerned. But in the context of Hellman’s tale of greed, stupidity and excess, this difference is also at the heart of what made Rudy’s or any other wine forger’s crimes possible and more likely to succeed than other types of counterfeit crimes. Once consumed, the original is gone. This makes a faker all the more likely to succeed.

Leave a Reply