A Comprehensive Review of Power and Ideology in Alcohol Politics

There is a political spectrum within the alcohol industry. However, it’s not much like the ideological extremes of American political culture.

There is a political spectrum within the alcohol industry. However, it’s not much like the ideological extremes of American political culture.

The American polity is divided; polarized in a way I can’t recall before. It’s as though the electorate will root for their team, no matter how absurd or radical the deeds, desires or words attributed to the leadership of their tribe. The middle of the American political spectrum is a wasteland—a bowed middle and top-heavy on the ends.

While it would be interesting to compare alcohol politics to American politics and while this comparison might provide insight into both pursuits, my intent here is to explore the ideological breakdown of the former.

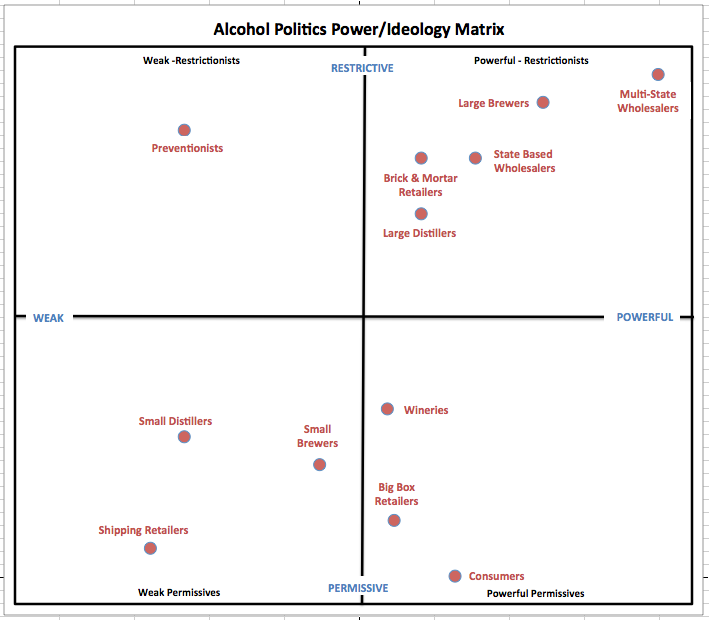

The politics of alcohol revolve around the question of regulatory control based on a Three-Tier System with the “Restrictionists” on one end of the political spectrum pursuing a strictly enforced Three-Tier System and the regulatory “Permissives” on the other end of the spectrum seeking a very loosely enforced Three-tier regulatory regime.

Key to understanding alcohol politics is recognizing the constituencies. They are primarily made up of producers, wholesalers/distributors, retailers/restaurants and consumers, and preventionists. Each of these constituencies possesses unique interests, but can also be divided into semi-distinct sub constituencies that pursue the larger constituency’s general interests more or less vigorously.

The distribution of political power among the various constituencies is determined by a somewhat complex set of factors. They include the way given alcohol laws protect certain constituencies from competition and the degree to which constituencies interact with the electoral process, to the extent a given constituency is politically organized.

The accumulation of power within alcohol politics is impacted by additional factors including the state of alcohol-related jurisprudence and its interaction with issues of interstate commerce, the universal commercial code, the First Amendment and the Commerce Clause. Moreover, as any single constituency successfully pursues reform or change to the alcohol regulatory system, the accumulation of power by other constituencies can be significantly altered.

While American political theater is played out in large part on the federal level with Washington machinations controlling the lion’s share of attention, in alcohol politics the theater is almost exclusively played out on the state level. This is due to the grant of power to the states to control alcohol policy found in the second paragraph of the 21st Amendment. While excise tax policy occasionally draws the alcohol industry’s attention to Washington and the federal bureaucracy, it’s in the state capitols where the alcohol industry’s political power and pursuits are most commonly on display.

A general assessment of a constituency’s power and place on the ideological spectrum of alcohol politics can be outlined with some precision (which I plan to attempt below). However, there can exist significant variations, particularly in degrees of power among constituencies, within each state based primarily on a state’s regulatory framework.

CONSTITUENCIES IN ALCOHOL POLITICS

Over time the number and type of constituencies in alcohol politics have changed. For example, closely following the passage of the 21st Amendment in the 1930s and well into the second half of the 20th century, there were few if any multi-state wholesalers. The same can be said for Big Box Retailers, which did not exist up until roughly the 1980s.

At this moment in time, I can identify twelve different constituencies within the alcohol industry that all seek to influence alcohol policy to one degree or another depending on their location on the ideological spectrum and the varying amounts of political power they possess:

• Wineries

• Big Brewers

• Small Brewers

• Large Distillers

• Small Distillers

• Multi-state Wholesalers

• State-based Wholesalers

• Big Box Retailers

• Brick & Mortar Retailers

• Shipping Retailers

• Consumers

• Preventionists

Below I want to explore each of these constituents inside the realm of alcohol politics. I want to outline where they sit on the ideological spectrum and why, as well as their degrees of power and what impacts how they wield that power in attempts to gain advantage and impact alcohol policy.

This assessment will be entirely my own based on my 25+ years worth of observation of alcohol politics as well as working through personal efforts as well as organized efforts to impact and influence alcohol politics in various states. However, first I want to delve a little deeper into the ideological spectrum of alcohol politics and how power is won and wielded.

IDEOLOGICAL SPECTRUM OF ALCOHOL POLITICS

As I noted above, the most obvious and instructive way to understand alcohol politics is to place it within the context of regulatory control of alcohol distribution and sales, based on the degree to which a traditional three-tier system is strictly or loosely enforced. Another way of stating it is that the ideological spectrum on which alcohol politics play out is based on a restrictive view of competition at one end of the spectrum and a permissive view of competition at the other end.

Extreme “Restictionists” support the imposition of alcohol laws that severely restrict how the three tiers (producers, wholesalers, retailers) interact with each other as well as how they can interact with consumers. For example, the extreme Restrictionist would outright oppose any retail sales of alcohol other than those that occur in person at a brick and mortar retailer. The extreme Restrictionist would also demand that brick and mortar retailers always and only purchase their inventory from an in-state wholesaler.

The extreme “Permissives” on the other hand pursue and advocate for a regulatory system that allows a wide variety of options within each tier for sales and distribution of alcohol. They will support self-distribution that allows all producers to sell directly to retailers and restaurants without any obligation to sell to a middleman wholesaler. Permissives will also support interstate sales of alcohol, particularly to consumers via direct shipment, but also interstate self-distribution of alcohol.

Not all players in the alcohol industry are extremists occupying one end or the other of the ideological spectrum. The degree to which a constituent exists more toward the middle in its ideology and advocacy is largely a function of pragmatism. For example, while some producers would support unrestricted sales to consumers without having to first sell their goods to wholesalers who then will mark up the product before selling to retailers, they may not actively advocate for this policy since their more immediate goal is to obtain self-distribution rights inside their state of residence. This priority can often lead them to support restrictive direct sales policies in exchange for more permissive self-distribution policies. This kind of practical ideological moderation occurs regularly in the alcohol industry.

Finally, the ideological spectrum of alcohol politics is, like American politics, constantly changing —though slowly. The changes that have occurred over time that have impacted alcohol politics are the result of technological innovation, society’s evolution toward a more permissive relationship with alcohol, the impact of a more conservative legal interpretation of the meaning of the 21st Amendment, and a maturing of alcohol production standards influenced by increased consumer demand for higher quality products.

So for example, while years ago it would be commonplace for some members of the alcohol industry to successfully oppose direct sales of wine to consumers from winery tasting rooms, today this position is unsustainable. Also, when in the past it was common to opposition to sales of alcohol in grocery/food stores, today that position is untenable in most states.

In general, the ideological spectrum in alcohol politics has slowly moved to be slightly more permissive. Given the much more restrictive set of alcohol distribution and sales laws that existed when alcohol policy was re-invented after Repeal in the 1930s, this movement to a more permissive regime is not surprising. This is not to suggest, however, that political battles in the alcohol industry have diminished over time. In fact, the past 30 years have only seen the exercise of political power increase.

THE EXERCISE OF POWER IN ALCOHOL POLITICS

Despite the alcohol industry being among the most highly regulated in America, it is still an industry defined by competition and market share. However, due to its highly regulated nature, competition and market share is commonly manipulated by the rules of the game set down primarily by the laws of the states and the politicians in each state that maintain and make those laws.

The starkest manipulation of competition in the alcohol industry is a result of the degree to which a “three-tier system” is enforced in a given state. When a state maintains a more restrictive set of alcohol distribution and sale rules certain constituents benefit by being protected from competition, which in turn artificially increases their market share.

In states, for example, where products are more strictly required to flow from producers to wholesalers then to retailers, the middle tier enjoys a guaranteed transaction, as well as the ability to set prices and margins with less of an impact from competitive pressures. This, in turn, leads to easy access to greater revenue for the wholesaler constituency and a related diminishment of potential revenue by the producer tier.

On the other hand, when producers are relieved of the requirement to sell their products to a middleman and are instead allowed to sell directly to consumers, a transfer of revenue accumulates to the producer and with it increased political power.

The key, however, is that when regulatory policy produces a competitive advantage to any given constituency, a related transfer of political power also occurs. Increased revenue translates into increased resources for political organizing and advocacy, including participation in the electoral politics via campaign contributions and the political access it produces.

Finally, the accumulation and exercise of political power is also impacted by changes in the legal landscape. For many years, and to an extent still today, federal courts provided states with legal cover for highly protectionist laws governing alcohol sales and distribution. However, as courts have taken a more conservative view of the states’ grant of power over alcohol policy by the 21st Amendment, some of the opportunity for states and certain constituencies to institute protectionist, rent-seeking sales and distribution laws have been diminished.

In 2005 the Supreme Court ruled that states violate the Constitution when they enact protectionist laws that interfere with the federal government’s right to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling in Granholm v Heald radically altered the political power dynamic by providing producers (primarily wineries) with new more profitable sales channels. A more recent Supreme Court decision, Tennessee Wine v. Thomas, has extended this anti-protectionist principle to the retail tier that is likely to alter the political dynamic for retailers, particularly the type that engages in interstate commerce and direct shipment of alcohol to consumers.

THE IDEOLOGY AND POWER OF AMERICA’S PRIMARY ALCOHOL INDUSTRY CONSTITUENTS

Who wields the greatest power in the realm of alcohol politics? Where do the various constituents sit on the ideological spectrum? Which constituencies have seen their power diminish over time? Which constituency under-uses their power. These are the questions addressed below as I try to outline the individual position of 12 different constituencies actively working in alcohol politics.

Please take note of the matrix at the top of this post. It can be clicked and enlarged to be used as an accompaniment to what follows in understanding the relative position of each constituency in alcohol politics today. I again want to reiterate that this is my own view of alcohol politics derived from interacting with and observing the American alcohol industry for nearly 30 years. It does not represent the beliefs or views of any particular client or group.

WINERIES

Ideology: Moderately Permissive

Political Power: Above Average

While the vast majority of wine sold in the U.S. comes from a very small group of very large wineries that produce wine in the United States or import wine into the United States, there exists little in the way of a political divide between large and small wineries. While dependant upon wholesalers, large wineries have not pro-actively supported the three-tier system. It’s equally true that these large wineries have not actively advocated for self-distribution rights. Most political activity by this constituency has been aimed at direct shipping rights, which have largely been won due to the 2005 Granholm v. Heald Supreme Court decision and significant advocacy on a state-to-state basis with the additional allyship of consumers. While all wineries would benefit tremendously from augmented interstate self-distribution rights, even small wineries have not spent political capital advocating for an expansion of this sales channel. An important source of the political power of the winery constituency is derived from the fact that the vast majority of wineries in the United States are small, family-owned entities that are also farming families, a particularly sympathetic cohort that lawmakers generally support. The California Wine Institute, once dominated by the largest California wineries but more diverse today, wields the greatest political power nationally despite being a state-based organization. Its efforts are augmented by a national association of wineries, Wine America, as well as state-based and regional associations that advocate on a state level.

LARGE BREWERS

Ideology: Significantly Restrictive

Power: Highly Significant

The brewing industry in America is dominated by large, multinational brewers who wield significant political power due simply to their size, market share and extraordinary revenue base. Though this revenue base has been somewhat diminished over the past several decades by the emergence of small craft brewers, the Large Brewer constituency maintains significant power in alcohol politics and wields it in support of very restrictive policies that seek to maintain a strict three-tier system. Large Brewers who depend upon national wholesaler distribution have consistently opposed self-distribution, expanded taproom sales privileges as well as direct to consumer shipment of all alcohol, not merely for beer. Some of this advocacy has begun to change over the past few decades as the large brewers have purchased smaller, craft brewers to augment their portfolios and market share. It would not be a surprise to see large brewers moderate their advocacy for restrictive sales and distribution laws in the future.

SMALL BREWERS

Ideology: Very Permissive

Power: Below Average

The rise of craft beer has been one of the most significant developments in the alcohol industry over the past 30 years. As the number of small craft breweries in every state has increased and as the public’s support for the craft movement took off, the small brewer has become much more active in advocating for more permissive sales and distribution rights including in-state self-distribution, taproom sales and expanded sales from brewpubs. Almost always the small brewers have found themselves in political battles with the much more powerful state wholesalers who have nearly universally opposed expanded sales and distribution rights for brewers. The small brewer has been most successful in securing the right to sell what are often limited quantities of beer from their taprooms and brewpubs. They have been supported by state lawmakers in this effort as the difficulty of expanding business when tied to a strict three-tier distribution routine is made clear. In addition, craft brewing has proven to be an economic accelerator for cities and regions. Still, the small brewer constituency remains somewhat politically weak though that power appears to be on the increase. The small brewer has yet to accumulate enough political power to institute widespread self-distribution rights, which is currently a key goal for small brewers in most states. To-date, small brewers have made little or no attempt to liberalize state direct shipment laws, directing their political capital towards self-distribution and taproom privileges. Nationally, the Brewers Association represents the country’s small brewers. However, most political power is wielded by state-based craft brewer associations that are often underfunded.

LARGE DISTILLERS

Ideology: Somewhat Restrictive

Power: Above Average

America’s large Distillers, like the country’s large Brewers, are a relatively small group, yet their large market share provides them with a good deal of political power. These largest distillers, along with their overseas counterparts that import significant amounts of spirits and command a large share of the market, are very strong supporters of a strictly enforced three-tier system. Their influence, particularly on issues of prevention as well as excise taxes, are considerable. However, they have not flexed their muscles in any considerable way where it comes to combatting the efforts of the growing number of small, craft distillers who are just now beginning to flex their muscles. This is due in part to the fact that the large distillers do not have a large presence in many states. The Distilled Spirits Council, which represents the large distillers, displays a more conspicuous presence in Washington, DC where their influence can be significant.

SMALL DISTILLERS

Ideology: Solidly Permissive

Power: Somewhat Weak

America’s small distiller constituency has only recently begun to flex their small, but growing muscles. As the craft distilling industry has exploded in the United States with the support of consumers, small distillers have begun to voice their opposition to restrictive laws that have long governed spirits sales and distribution. As with small brewers, small distillers find themselves battling state wholesalers who have largely opposed the small distillers’ desire to liberalize self-distribution and direct to consumer sales. Where the small distillers have been successful in liberalizing these laws, they have had to do so with significant restrictions. Small distillers have yet to make any effort to change laws concerning interstate direct to consumer shipping, which would benefit the constituency considerably. Most advocacy takes place at the state level where the relatively small size of most craft distillers hampers their efforts. However, their “mom and pop” impression is and will continue to create sympathy for them among lawmakers in the same way that small wineries benefit from their “family farmer” status. As with their larger brethren, smaller distillers are most actively involved in lowering federal excise taxes. This effort will take up the bulk of their political capital until the issue is satisfactorily resolved, at which point it is likely their next target for advocacy will be self-distribution and direct sales efforts.

MULTI-STATE WHOLESALERS

Ideology: Extremely Restrictive

Power: Very Powerful

The remarkable and sustained power of America’s multi-state wholesaler constituency is based primarily on a decades-long grant of protection from competition by nearly every state government in the country. This is sufficient to explain these large wholesalers’ extremely restrictionist ideology and consistent defense and advocacy of a strictly enforced three-tier system. That long-term protection from competition along wth significant consolidation over the past two decades has resulted in significant monetary resources that are regularly spent on an accumulation of political capital. Today’s few but powerful multi-state wholesalers are among the most generous contributors to political campaigns in both Washington, DC as well as the individual states. In return, they are granted political access to defend their ideology of strict enforcement of the three-tier system where all alcohol flows through them. These wholesalers with multiple billions in revenue are represented by the Wine & Spirit Wholesalers of America and the National Beer Wholesalers Association. Despite their power, political access and protection from competition in many markets, the multi-state wholesaler constituency has seen their advocacy for a strict three-tier system of alcohol distribution and sales successfully attacked over the past twenty years. The source of that attack has largely been a federal judiciary that has poked good-sized holes in the wholesalers’ argument that protectionist state laws long benefiting them are immune from review under the Commerce Clause. The 2005 Granholm v Heald Supreme Court decision and the 2019 follow-up and extension of the Court’s anti-protectionist jurisprudence in Tennessee Wine v Thomas both struck at the heart of the wholesalers’ pro-protectionist and state’s rights dependancy. Still, the multi-state wholesaler constituency wields considerable power and they are likely to for the foreseeable future.

STATE-BASED WHOLESALERS

Ideology: Very Restrictive

Power: Very Powerful

Despite the significant power of the multi-state wholesalers constituency, it is the state-based wholesalers that do the lion’s share of political advocacy for a strictly-regulated three-tier system. The state-based wholesalers have also long enjoyed the protectionist legal framework that is the three-tier system and has accumulated significant political power as a result. However, despite their hard and often successful work defending the three-tier system and stymieing the desires of smaller producers from finding a way to market around them, they have seen their political power diminish in a number of states over the past two decades. While still welcomed in state capitals and often consulted on any alcohol-related legislation, the state-based wholesalers have also seen their ideological commitment to restrictive alcohol policy partially upended by judicial decisions and even by consumer mandate that has weakened a once impenetrable three-tier system of alcohol regulation. While some state-based wholesalers still enjoy tremendous political power others have seen their power diminished as various forms of self-distribution and direct to consumer sales have been instituted and supported by the growing number of small beer, wine and spirit producers and their consumer allies.

BIG-BOX RETAILERS

Ideology: Moderates

Power: Relatively Weak

Thirty years ago there were few if any Big Box Retailers, and certainly no multi-state big-box retailers. Today there remain very few. However, they are responsible for a significant percentage of wine sales in particular as American consumers have embraced the chain, big-box culture. Ideologically the few big-box retailers that sell significant amounts of alcohol have remained relatively moderate in their political advocacy. Most of their efforts have been spent attempting to beat back various state restrictions on who may obtain licenses to retail alcohol and how many they may obtain. When most state’s original alcohol laws were established in the 1930s to 1950s, big box stores were not contemplated. Moreover, the few big-box retailers have not used cooperation and association to advance their ad-hoc political interests. Their large size and their small numbers have made them important, but essentially political loners. On occasion, big-box retailers have taken on entrenched interests in significant ways, whether it be essentially deconstructing a three-tier system in Washington State or taking on and beating back long-cherished residency requirements in federal court. It is notable that while big-box retailers are extraordinarily well-positioned to enter the direct-to-consumer alcohol shipping market, they have largely stayed away for advocating for retailer shipping rights. The cynical explanation for this position is that given their cross-state footprints, they have nothing to gain by supporting more liberal interstate shipping laws for all retailers.

BRICK & MORTAR RETAILERS

Ideology: Very Restrictionist

Power: Significant

The brick and mortar constituency is made up of primarily corner liquor stores and provincial fine wine stores. They represent, by far, the largest majority of alcohol retailers in America and wield significant political power in state capitals. Like the small wineries and craft alcohol producers, brick and mortar retailers benefit politically as being perceived as small, family-run institutions. From an ideological perspective brick and mortar retailers have long tied themselves to the restrictionist wagon championed and led by both multi-state and state-based wholesalers. They have opposed all movements to open direct to consumer shipping by out-of-state producers and retailers. Counterintuitively, brick and mortar retailers have never been in the lead to open self-distribution channels from producers to retailers, as this would negatively impact their alliance with state and national wholesalers. Nearly every state has at least one and sometimes two or more regional associations that represent the interests of the restrictionist brick and mortar constituency. Notably, brick and mortar retailers lot a significant court battle in 2019 when the Supreme Court ruled against the Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association (and in favor of a big-box retailer) on the issue of residency requirements for Tennessee retail licensees. The political impact of the Tennessee Wine v Thomas case has not yet fully played out, but by all indications, it is likely to diminish the brick and mortar retailers going forward.

SHIPPING RETAILERS

Ideology: Extremely Permissive

Power: Weak

America’s shipping retailers constituency displays a relatively single-minded pursuit of interstate shipping rights. Though primarily made up of independent fine wine retailers along with some internet-based retailers, the shipping retailers constituency evolved out of the rise of e-commerce and diverse alcohol delivery options. Though focused primarily on the issue of interstate shipping, this small group of retailers also supports extremely permissive sales and distribution laws, including self-distribution for all producers. Their relative weakness is due in large part to their small numbers, which translates into smaller resources. In addition, their advocacy is almost always viewed by lawmakers and other retailers as unjustified, out-of-state competition that generates little sympathy. The shipping retailers have been very active supporting lawsuits challenging protectionist state bans on interstate shipments of alcohol. They have had some success and a number of losses in the courts. However, they have been the most consistent political advocates for and intellectual supporters of an alcohol distribution system that does not have the three-tier scheme at its heart. Shipping retailers are represented by the National Association of Wine Retailers and announced vindication of their ideology when the Supreme Court ruled against protectionist alcohol policy in its 2019 Tennessee Wine v Thomas decision.

CONSUMERS

Ideology: Extremely Permissive

Power: Relatively Powerful

American alcohol consumers have been the silent power in Alcohol politics since the repeal of the 18th Amendment and the end of Prohibition. However, it is extremely rare for consumers to make their voices heard in the realm of alcohol politics. Yet when do speak out, they are almost always in favor of more liberal sales and distribution laws and occasionally upend long-standing distribution systems. Over the past 25 years, the number of “dry” precincts in American states has continually dwindled due to a lack of consumer support. Consumers have shown support for the introduction of wine and beer into grocery stores where it had long been absent. Consumers were also responsible for tearing down Washington State’s three-tier system in a referendum vote in 2011. After the 2005 Granholm v Heald Supreme Court decision that struck down restrictionist wine shipping laws, consumers played key roles in convincing legislatures to open up their states for the direct shipment of wine. There is no general “consumer union” for wine consumers. However, “Free the Grapes” was very successful in rallying consumers in favor of more liberal direct shipping laws. Currently, WineFreedom is attempting the same consumer alliance on the issue of retailer direct shipping. Still, consumers—including alcohol consumers—are notoriously difficult to rally to political action. However, the past has demonstrated that if the other permissive alcohol industry constituencies can motivate the American wine consumer, they will be joined by a significant and powerful ally.

PREVENTIONISTS

Ideology: Very Restrictionist

Power: Weak

There was a time when the Prevention (including the health) constituency was the most powerful voice in alcohol politics. Those advocating for a restrictive alcohol policy were the most responsible for the onset of Prohibition and also played an enormous role in the restrictive laws that were put in place to control alcohol and prevent abuse in the wake of Repeal. Today the Preventionists play only a small role in the development of alcohol policy. Including numerous government health and safety officials, some national organizations devoted to the anti-alcohol cause and most law enforcement officials, the Preventionists do still attempt to make their voice heard where alcohol policy is made. They have generally supported very restrictive sale and distribution laws and opposed direct to consumer shipping. They are often seen allying with wholesalers on various issues but break with this and other alcohol constituencies when it comes to excise taxes, which they support in their higher form. The weakness of the preventionists is due to a variety of factors. Most important is that often their attention is divided between various issues. They also are often underfunded in their anti-alcohol efforts. Preventionists have gained some traction recently on the issue of blood alcohol levels as applied to drunk driving laws. They advocated for and successfully accomplished lowering the blood alcohol level to .08 from .10 and are currently working in a number of states to further strengthen the drunk driving laws by lowering the blood alcohol limit to .05.

INTER-CONSTITUENCY SUPPORT

It is a unique dynamic that those falling into the “Permissives” camp very rarely work together or consistently act as allies, while those in the “Restrictionist” camp have found great success in consistently working together on numerous policy initiatives. The explanation lies mainly in an examination of competitive impulses.

It’s a key observation that those on the Restrictionist side of the ideological spectrum are not consistent competitors. Yes, big brewers compete with big distillers for market share, however, it is often the case that the largest distillers also own breweries, while the largest distillers have cross-ownership of breweries and wineries. Moreover, retailers don’t view wholesalers as competitors and vice versa.

Meanwhile, small breweries, wineries and small distillers have not found a way to band together, but instead, view the competition for market share by each of these constituencies in a much more stark fashion. It is extraordinarily rare to see distillers support wineries in their efforts to ship direct to consumers. Wineries and brewers have not spent any political capital aiding distillers in their efforts to sell directly to consumers at their distilleries. Oftentimes this is the case because changes to alcohol policy that might aim to liberalize self-distribution or direct sales laws are often only aimed at brewers or only distillers or only wineries. This lack of cooperation between producers and even between producers and retailers has played an important role in holding back more permissive alcohol sales and distribution policies.

THE FUTURE OF WINE POLITICS

The heavy regulation at the state and federal level explains the relatively conservative nature of the alcohol industry as well as the fact that alcohol industry economics and innovations trail almost all other industries. This is unlikely to change going forward. However, if you want a glimpse of the future of alcohol politics, the issues that will rise to the top an the kind of change the politics are likely to bring, simply look at the most common changes that have come to most other industries.

E-commerce in the Alcohol industry now stands at somewhere between $3.5 and $5 billion in the United States. This is very likely to increase and at a rate equal to or faster than the overall increases in e-commerce across all other sectors of the economy. It’s not that the alcohol industry does not know how to use e-commerce to sell wines, bourbons, and IPAs. It’s a matter of alcohol regulations and alcohol policy allowing interstate shipments have been stymied for years. However, the constituencies currently opposing alcohol shipments are in a losing battle against the courts and consumers.

It’s also likely that self-distribution rights for alcohol producers will expand in the coming years. Those who most desperately need to pursue self-distribution, small brewers and small distillers, have not yet fully turned their political attention to this issue. When they do they will have the support of a motivated consumer base that is better prepared than ever to challenge the Restrictionists that want to see the three-tier system maintained.

Additionally, anyone observing the alcohol industry that does not see further consolidation at the wholesale tier and with it increased power by the multi-state wholesalers doesn’t understand the concept of inertia. The Southern-Glazers, Republic-Nationals, Breakthrus and Young’s Markets of the world are on a path to “bigger” and will pursue that path with significant vigor. This, in turn, will divert even more revenue into fewer hands that will result in even greater political capital among a small number of dominant multi-state wholesalers. How this consolidation will play out on the individual state level is not yet entirely clear. Currently, the state-based wholesalers constituency enjoys a certain sympathy for being locals. As the in-state wholesalers are gobbled up by larger multi-state wholesalers that political sympathy may or may not continue to exist. And as fewer and fewer wholesalers control the distribution of alcohol, there is a question of whether the brick and mortar retailer constituency will continue to throw in with what is surely to be a more aggressive wholesaler.

Finally, there is the question of the Courts. Over the past two decades, federal courts have played a critical role in the slow redistribution of political power to producers and away from wholesalers. The recent Tennessee Wine v Thomas decision at the very least will continue that trend and at most might upend the structure of alcohol distribution and sales.

# # #

Since the Supreme Court rendered its Tennessee Wine v Thomas decision in June, I’ve been thinking much more about the dynamics of alcohol politics. I believe it is likely this decision will bring significant changes to both alcohol sales and distribution as well as alcohol politics. This post is the result of that thinking about the current state of alcohol politics.

Link Shortener Amazon

[…]very few sites that come about to be detailed below, from our point of view are undoubtedly very well worth checking out[…]